I was born in Kyerwa District in northwestern Tanzania, where schools were far away and essential services nearly non-existent. I didn’t start the 1st school class until the age of nine—not because I wasn’t ready, but because I had to wait until I was strong enough to walk several kilometers to the nearest school. When I finally got there, I found a bare classroom with no desks or chairs—we sat on the dusty floor, trying to learn. There was no food offered, so hunger gnawed at us until noon when we began the long walk back home. It took extra commitment just to stay in school and avoid dropping out. Those early hardships taught me a lasting truth: that geography and poverty can severely limit opportunity. But they also planted the seed for the work I do today.

After secondary school, getting into university was another struggle. Coming from a low-income family, I relied entirely on a government loan to continue my education. However, the government only funded certain “priority” courses—and my first choice, pharmacy, wasn’t among them. I was denied the loan. I reapplied and received funding to study teacher education instead, but after just two weeks, I withdrew. Teaching wasn’t my passion. In Tanzania, teachers often earn low salaries and are unfairly viewed as those who didn’t perform well in school. Unlike my first choice of pursuing pharmacy, this is always considered of high value and contribution in the community. Missing my first choice, I couldn’t see myself thriving in the teaching path. The following year, I tried again and was accepted into a course I truly cared about—Natural Resources Management. That was well tied in my childhood as we used to hunt small animals like gazelle and rabbits with my friends in the village forests and bushes. It was not only for obtaining bush meat but also a fun activity during the weekend. I began my BSc. in Wildlife Management, learning that the fight for education isn’t just about access—it’s about pursuing what you love.

After graduating in 2015, I returned to rural life—not to escape it, but to help transform it. I got my first job with the Catholic Diocese as a Project Officer in the Department of Agriculture and Environment, on a two-year contract from mid-2016 to mid-2018. I worked closely with smallholder farmers across Biharamulo District, delivering trainings on sustainable agriculture. While working at my first job assignment one afternoon while conducting training in a remote village, a woman approached us. She had a baby on her back and a pot of food on her head. She explained that she was taking food to her sick husband at Biharamulo Hospital—21 kilometers away—and asked my supervisor for a ride. The car was nearly empty, but my boss declined harshly, saying, “Usingeniona je?” (“What if you hadn’t found me here?”). His words stung me. I felt powerless to intervene, but something inside me shifted. I realized that people in rural areas suffer—not from lack of will, but from lack of access, empathy, community awareness on income generation, capital to start small ventures and limited voices of change. Something in me said that I need to be part of the solution.

When my contract ended four months later, I began the journey to establish my own community-based organization. In 2018, I launched an initiative grounded in three thematic areas: women’s empowerment, sustainable agriculture, and environmental protection. We began as a district-level civil society group, and in 2021, we secured full registration as an NGO (Non Governmental Organization): Participatory Livelihood Improvement, Ecology and Sanitation (PALES) – www.pales.or.tz, Facebook (Registration No. ooNGO/R/1670).

Since then, PALES has grown from a village initiative into a recognized grassroots organization working to empower women, improve rural livelihoods, and protect the environment. We’ve implemented three major community-based projects, each rooted in the realities of the people we serve. While none of them reached their full potential due to limited funding, their impacts were real—and the need remains urgent.

The first project we launched in 2018 was inspired by my experience in Biharamulo community. The Musenyi Women project implemented in Musenyi village, aimed to economically empower women and girls through improved vegetable farming, chicken rearing, and goat keeping. We worked with 210 women across 11 groups and actively involved men to promote shared ownership within households. The project brought real change: some women could, for the first time, afford school supplies and shoes for their children. “Now my children walk to school with shoes,” one mother told me, “and I feel proud.” Sadly, the project ended midway in 2021 due to lack of funds. Yet, its importance is still felt in Biharamulo. We continue to seek partners to help us revive this life-changing initiative. Partners who could support us with seed capital to start small sustainable ventures like keeping goats, pigs, cows, chicken rearing and vegetable farming. Also support with technology, knowledge and machines to produce bananas, sweetpotatoes, cassava and sunflower.

In the course of implementing the first project, another urgent need for intervention raised, which was transformed into the JamboMama Project. This maternal health project focused on reducing home deliveries and maternal deaths in Runazi Village. Working alongside the local dispensary, we envisioned a digital tool—a mobile app—that would allow pregnant women to remotely consult doctors or nurses. It gained traction quickly, with many seeing its potential to bridge the rural health gap. But after a year of operation, the individual donor supporting the project ran out of funds and paused her commitment, promising to return once she found new backers. We are still waiting. Jambomama remains a critical idea that could save lives, and we welcome partners to help us bring it back to life. Partners to support PALES with funds to continue awareness campaigns on maternal health and start a charitable shop that brings delivery items close to the pregnant mothers at an accessible price.

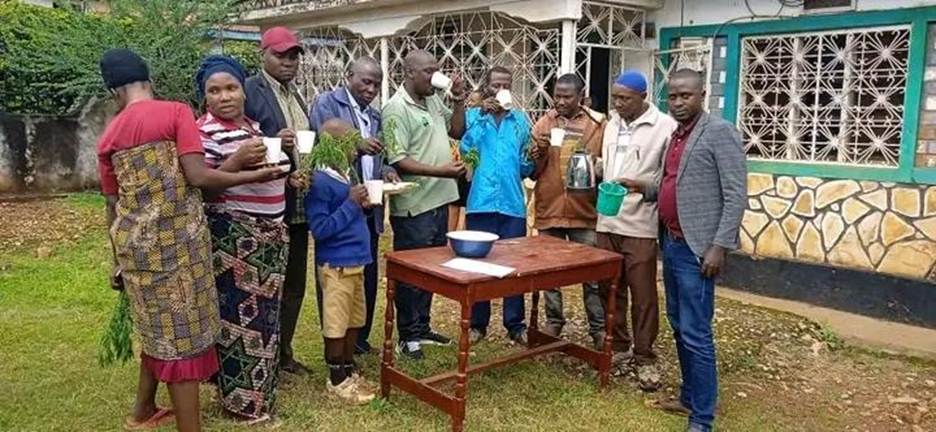

While interacting with health service providers at Runazi dispensary, it was learned that Malaria records number one disease in the area. It was not shocking news as the entire country is prone to Malaria. Malaria medicines are expensive and sometimes unavailable in our local dispensaries. Pregnant mothers and children are at high risk of death for Malaria. On that question, Artemisia herbal medicine comes in mind and it was the beginning of Artemisia project. This initiative aimed to fight malaria using community knowledge and herbal medicine. With support from The House of Artemisia (France), we trained villagers to grow Artemisia annua, a medicinal plant known for its anti-malarial properties. The donor provided only seeds and technical know-how, as per their policy. Our pilot was a success—we cultivated enough seed for future expansion. However, to scale up and embed these practices across the community, we now need financial partners. This low-cost, locally rooted solution to malaria prevention is ready to grow—we just need the resources to make it happen. Resources such as machines for processing and packaging of Artemisia tea as well as transport costs and training materials to spread the news.

My leadership journey has been shaped by powerful communities and generous mentors. At the 2024 MasterPeace Bootcamp in Romania, I met Dr. Nico de Klerk, who encouraged me to join the Be a Nelson movement. Through StreetBiz, I completed a course in social entrepreneurship, gaining tools to grow our vision. I also benefited from my other network organizations such as Lightup Impact, where I strengthened my ability to communicate impact, and from Metis, which helped me improve my impact presentation skills.

Of course, challenges persist. Lack of mentorship often means learning through trial and error. Limited funding delays promising ideas like Darasa Mtaani, a project to equip girls and young mothers with employability skills. And without consistent access to conferences and peer learning, I often build my skills in isolation.

Still, I remain committed. I have seen what’s possible when rural women are empowered with skills and dignity. I believe that change doesn’t come from the top—it rises from the ground up, just like it did in our projects.